OPINION: Eviction process in Florida broken for those struggling during the pandemic

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced March 29 the extension of the federal eviction moratorium through June of this year.

The order was originally called for to ensure Americans could avoid eviction and have a place to self-isolate in hopes of mitigating the COVID-19 crisis. However, it has accomplished virtually nothing in Florida since the state’s moratorium expired six months ago and Gov. Ron DeSantis failed to extend the ban into 2021.

This federal moratorium’s failure to effectively aid in the ban on evictions could be affecting USF students who have lost their sources of income and can no longer pay for off-campus housing during the pandemic, as 85% of undergraduates in the 2019-20 school year lived off campus, according to USF’s Common Data Set Report for that year.

Florida’s state moratorium expired in October 2020 and since then the number of eviction filings has increased to reach the same as it was pre-COVID-19.

While the state and federal moratoriums were in place in April 2020, the number of eviction filings was no more than 303 in Tampa, according to the Eviction Lab at Princeton University, a nationwide database of evictions.

Compared to the average of 1,252 filings in April 2016-2019, this decrease proved that having the state and federal moratoriums helped the eviction crisis in Florida. By the end of last year, though, filings reached 1,356 during the month of November.

It seems once the state ban on evictions was lifted, the federal moratorium had no real power in Florida to stop tenants from being dragged into court and put through the eviction process.

Unlike the Florida moratorium, the CDC’s federal moratorium order puts the responsibility on the tenants to prove they should not be evicted.

The order doesn’t stop landlords from being able to take tenants to court and also forces tenants to submit a statement of declaration that includes five qualifications to their landlord, including proof they lost their main source of income or experienced a large medical bill and proof they used their “best effort” to obtain all available assistance from the government.

But in Florida, some tenants aren’t even given the chance to go into court to defend themselves in the first place.

Individuals fighting evictions need to pay the money they are accused of owing into the courts to stand in front of a judge. If they are unable to deposit the rent money to the court, they are ineligible to defend their case and thus end up getting evicted, according to Florida Statute 83.232.

If they could pay their rent, they wouldn’t be in this situation to begin with. This statute clearly defeats the entire purpose of filing for the moratorium in the first place.

Some tenants also face issues of lease termination, which is when a landlord refuses to renew the lease for a current tenant. Since the CDC order does not address possible lease termination as part of its covered moratorium and only discusses “nonpayment” during the lease term, tenants can’t stop their landlord from canceling leases.

This means Americans with monthly leases possibly do not benefit from the federal moratorium at all. It also gives landlords the ability to kick tenants out of their homes if they don’t want to renew their lease for nonpayment.

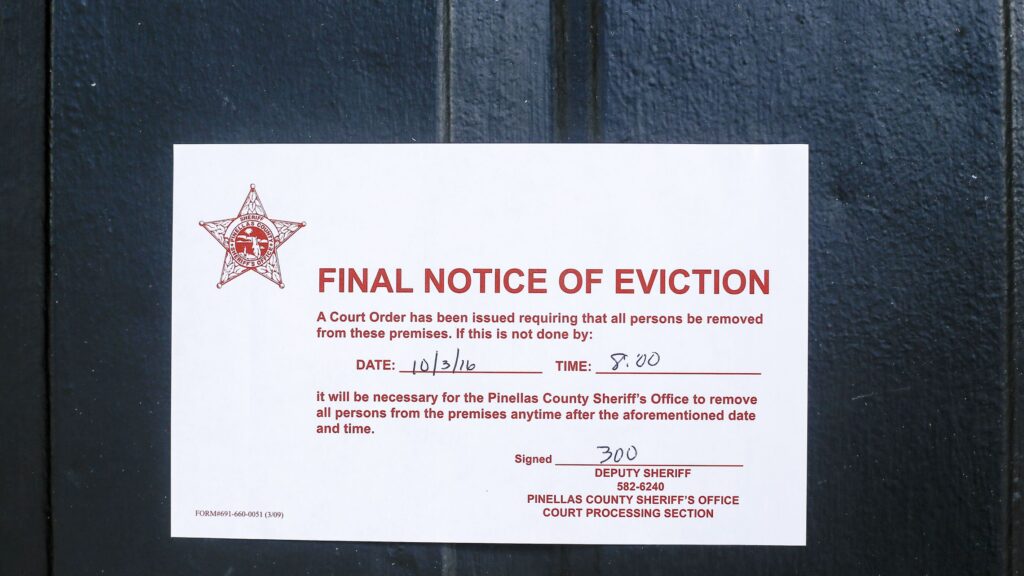

The federal order allows the eviction process to continue for those not facing lease termination as well, but it doesn’t allow landlords to post 24-hour eviction notices for tenants to vacate their residences. Although this may seem like a positive move, it’s short term and doesn’t protect struggling Floridians from the long-term consequences of an eviction.

When trying to apply for new leases, evicted tenants could be denied leasing rights based on previous evictions. The looming threat of homelessness coupled with a court case and lawyer fees could also take a serious toll on their mental well-being.

Once the moratorium ends, many of these people will have to consider affordable housing options to avoid becoming homeless. But the Florida Legislature is making sure they may not be able to take that route with recent changes made to allocations designated specifically for affordable housing projects.

Senate President Wilton Simpson and House Speaker Chris Sprowls are looking to permanently divert over $400 million from affordable housing to flooding and wastewater projects, which just happen to be on each legislator’s list of priorities this year, according to the Tampa Bay Times.

These projects are important to address, but taking funds away from affordable housing initiatives shows that Florida’s representatives are completely disregarding the seriousness of an impending statewide eviction crisis.

Swift action needs to be taken to ensure the security of current tenants so they are able to fight their evictions in court without having to pay rent money they don’t have. New bills need to be introduced to aid renters from being denied leasing rights based on evictions that occurred during the pandemic as well.

One bill, SB 576, has already been filed by state Sen. Shevrin Jones to stop landlords from denying applications to rent from those evicted during the pandemic.

This is a great first step and needs to be passed, but DeSantis also still needs to reinstate the moratorium in Florida. The state moratorium didn’t allow for evictions to be executed and taken to court like they are now, so this would be a weight lifted off of many citizens’ shoulders if they don’t have to fight to keep a roof over their heads.

State projects that provide aid to renters and affordable housing also need to keep their established budget, and legislators need to reject any possible cuts. Right now, the main concern for Floridians should be to stay safe and healthy until we can vaccinate everyone and try our best to return to normal.