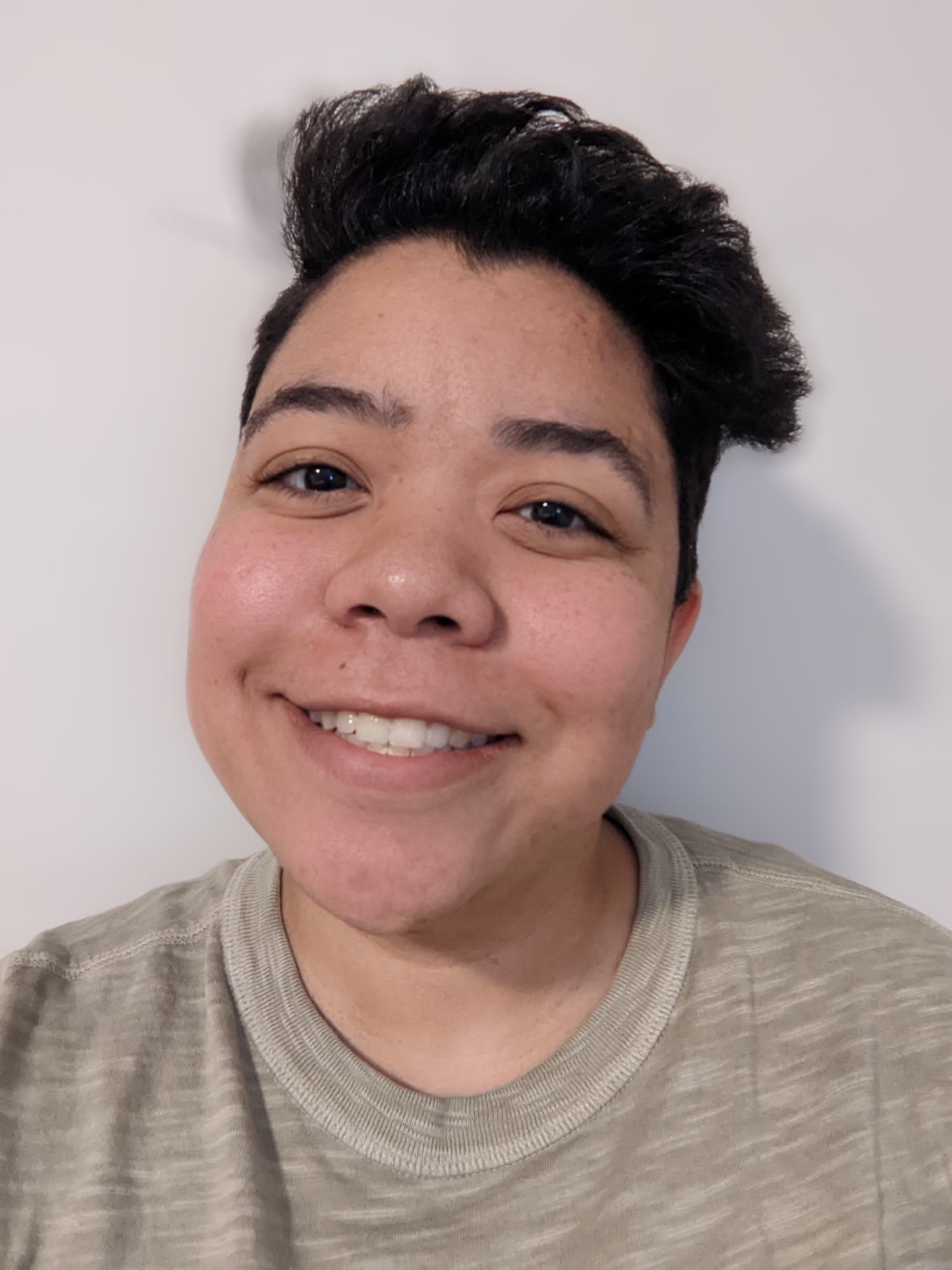

Power through Pride: Logan Fields advocates for LGBTQ intersectionality through community organizing

Despite the impact he has made in furthering inclusivity among on-campus queer organizations, computer science PH.D. student and president of the Queer and Trans People of Color Collective (QTPOCC) Logan Fields said he never envisioned himself directly engaging in activism when beginning his doctoral degree at USF.

Fields completed his undergraduate degree at FAMU, a historically Black college and university (HBCU), prior to transferring to USF to continue his postgraduate research career. Although he expected to find a similar sense of community given the diversified nature of USF’s student body, he said he was surprised by the lack of racial diversity in LGBTQ organizations and their respective leadership boards.

“There’s quite a few queer organizations on campus, which are all fantastic in their own way, but a lot of these organizations are also very niche. We have organizations for pre-medical students, for trans students and for LGBTQ communities and pride,” he said.

“But what I found, especially with coming from an HBCU, was that there was not a specific organization or a specific kind of codified space for queer students of color. That was something that the Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA) was working really hard towards … but there wasn’t necessarily a space for queer students of color to convene together.”

After sitting down with his friends to explore new clubs to join, Fields said he felt inspired to create a space for queer students of color that had been underrepresented. Alongside one of his friends, he formed the QTPOCC in March 2020 as a partnership with OMA.

In contrast to other LGBTQ organizations on campus, Fields said the collective’s primary objective has been to not only provide club members a sense of belonging, but a historical background of queer social movements led by people of color.

Advocating for intersectionality has always been an inherent aspect of his identity, according to Fields. While support for learning more about LGBTQ history has risen in recent years, he said the exclusion of racial minorities from much of queer history has motivated him to continue fighting for equal representation.

Former USF student and Fields’ wife Tori Clayton said her husband’s desire to help others can be felt both in his work and at home, where herself and Fields can often be found reading various science fiction novels together. As she struggles with her mental health, Clayton said Fields never fails to stand steadfast as a pillar of emotional and psychological support.

“Logan’s equally warm as he is focused and he’s the sort of person that loves with his whole being. He’s a generous, loyal person in a way that makes his friendships more familial and casual,” she said. “At home, he has been a strong ally during some of my weakest moments. He is always there with a kind word or patient ear whenever I need it most.”

His success in community organizing is something Fields said often requires him to reflect upon the adversities he has overcome. He said although he has faced various forms of discrimination given his identity as a Black and queer individual, an experience during his undergraduate career served as the catalyst to his involvement in social advocacy.

A lack of protections for gender and sexual orientation under FAMU’s anti-discrimination policies during Fields’ freshman year allowed professors to verbally accost him and other queer students on the basis of their identities without recourse. From making comments about queer students’ appearances to questioning their sexual orientation outright, Fields said he often felt ostracized from his peers despite the sense of belonging he previously felt.

Enraged by blatant incidences of discrimination from their professors and university leadership, Fields and fellow queer students were able to organize a campuswide protest in support of stronger protections. As a result of Fields and his peers’ protest, FAMU became the first HBCU nationwide to adopt more inclusive language in their anti-discrimination policies the following academic year.

During his time as president of the QTPOCC, Fields said he has attempted to use his background in community organizing as an educational resource for club members. From informing students of different forms of protest to providing emotional support to one another in times of adversity, Fields said he hopes his fight for change can be recognized as a continuation of countless struggles for inclusivity.

“I think that every person of color has at some point found themselves being the only face of color in a room and that every queer person has at some point found themselves as the only queer voice known. Anybody who has an identity such as those would understand how isolating that feels and how freeing it can be when you find other people like yourself,” he said.

“If anybody is lucky enough to have never been a minority in a predominant space, then maybe they don’t understand how isolating that feeling is.”

Responding to those that question the value of separate spaces for queer people of color can at times be difficult, according to Fields. While the club continues to be open to all students interested in learning about inclusive LGBTQ history, he said preserving time for queer students of color to come together remains the QTPOCC’s intended purpose.

“Our organization is not meant to exclude anyone who wants to join, but to provide a space where queer students of color can specifically go and say ‘Yes, I know that I will find other students of color in this space, that I am not alone in this sea of predominantness, that this is why we exist and why finding community is necessary.’”

For Fields, the celebration of Pride Month represents both a positive step toward the future of LGBTQ rights and a potential threat to racial inclusivity in mainstream queer social movements. Proceeding into the future, he said he is optimistic people will be able to take inspiration from the initial intention of pride when mobilizing to fight for social change.

“The significance of Pride Month to me is that the intention of its formation is often overlooked. The first pride was a riot orchestrated by Black and brown trans women and lesbians and it has become so corporatized and whitewashed over the years that I think only recently people have started to get back to its roots, to taking to the streets in protest,” he said.

“To me, pride is being subversive and breaking through the barriers people put in front of you by any means necessary. Whatever one has to do to get through those barriers, I certainly don’t believe in respectability. Niceties cannot be prioritized when it comes to matters of human dignity.”